Parallel Construction in Federal Investigations: A Critical Tool for Defense

Unmasking the Hidden Pathways of Evidence: A Practical Guide for Paralegals and Attorneys on Detecting and Challenging Parallel Construction

before getting started, please subscribe to our X account at https://x.com/ParalegalsToday

Introduction

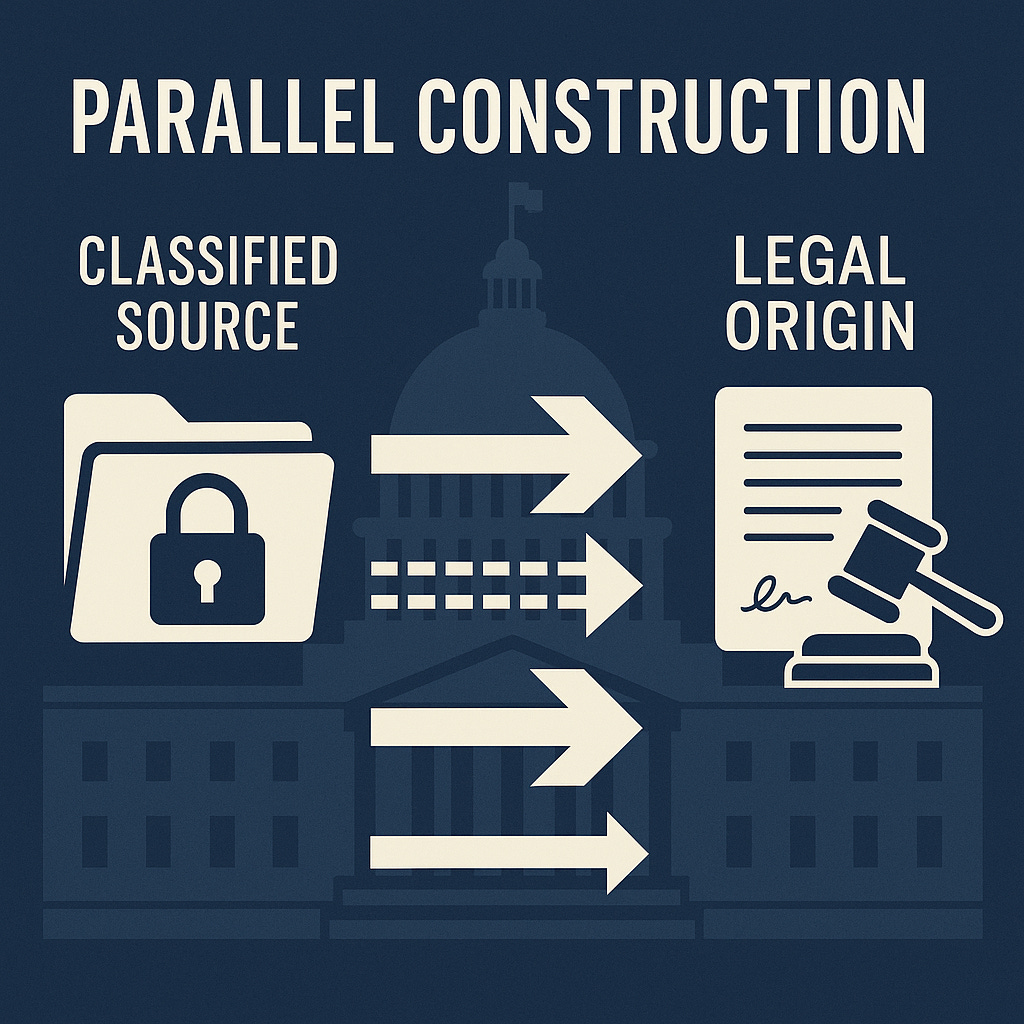

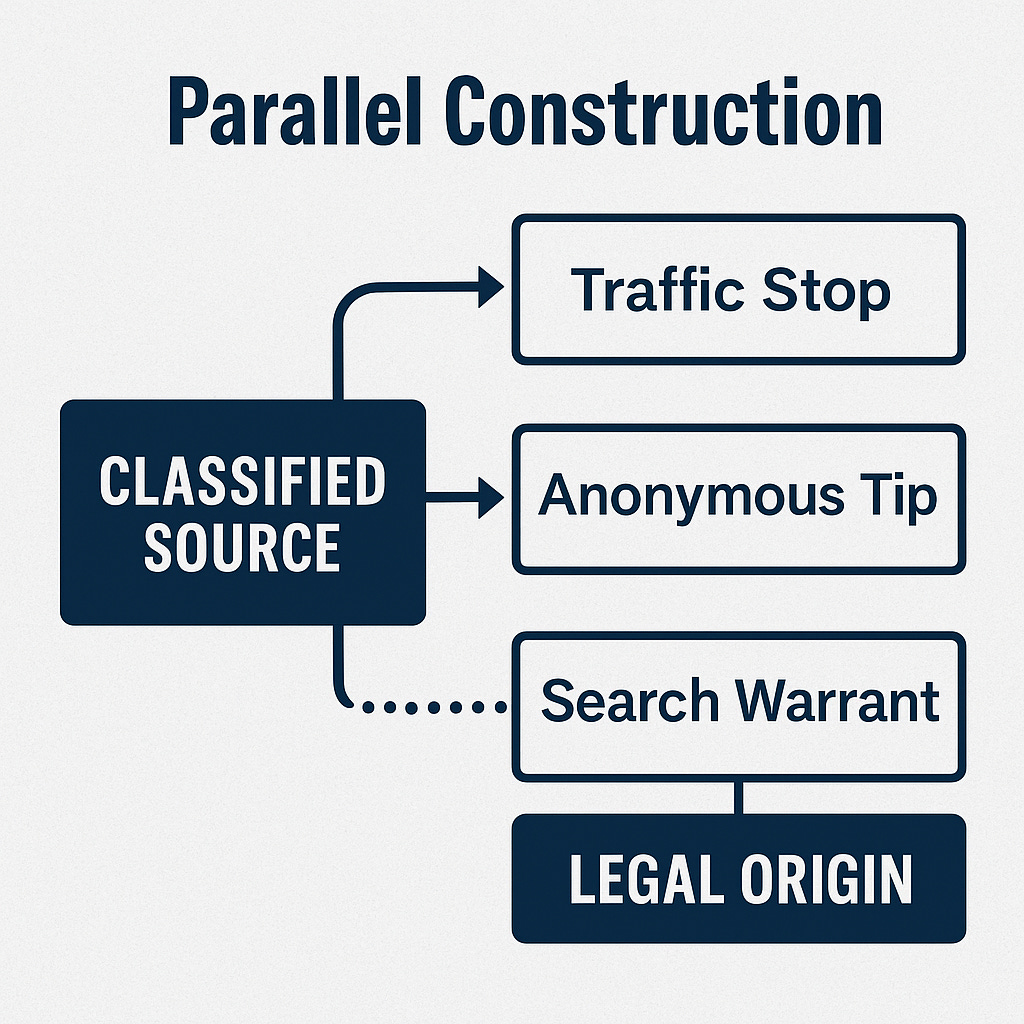

Parallel construction is a controversial investigative method increasingly used in federal criminal cases. Law enforcement begins with sensitive or classified intelligence—such as NSA intercepts or surveillance—and then recreates the investigative trail through conventional means, thus concealing the true origin of the evidence Eisner Gorin LLP, Wikipedia. This double-track approach not only sidesteps judicial scrutiny, but can also impair a defendant’s constitutional rights.

What Is Parallel Construction?

At its core, parallel construction is the process of building a second, apparent legal path for evidence to obscure its sensitive or unlawful source. For example, a secret intelligence tip may prompt agents to monitor a vehicle until a traffic violation occurs, providing a plausible—but misleading—justification for a search Wikipedia, BJCL.

Why It Matters to Paralegals and Attorneys

The practice has deep implications:

Fourth Amendment concerns: If the evidence originates from unlawful surveillance, any reobtained evidence remains tainted and potentially suppressible as “fruit of the poisonous tree” BJCL, Restore the Fourth Human Rights Watch.

Sixth Amendment implications: Concealed origins prevent the defendant from confronting the true source of evidence Eisner Gorin LLP, UNC School of Government.

Ethical integrity: Presenting reconstructed evidence as a genuine discovery may mislead the court and erode the justice system’s credibility Eisner Gorin LLP, Human Rights Watch.

Real-World Exposure

DEA and NSA: In 2013, Reuters exposed that the DEA’s Special Operations Division routinely guided agents to conceal tips from intelligence agencies and create legal alternatives Wikipedia, UNC School of Government.

Human Rights Watch termed it “evidence laundering,” highlighting its threat to privacy and judicial oversight UNC School of Government, Human Rights Watch.

Stingray case: In Florida, law enforcement’s reluctance to disclose the use of a Stingray device sparked a plea deal—highlighting how often—and how effectively—parallel construction can conceal methods. WIRED.

Case Law

1. United States v. Alverez-Tejeda (9th Cir.)

This is one of the most prominent judicial examples of parallel construction:

Facts: The DEA suspected Mr. Alverez-Tejeda of drug trafficking. Rather than seeking a warrant, agents staged a contrived traffic accident with government agents playing roles—“drunk driver,” “car thieves,” the whole scenario—to manufacture grounds for a lawful search. The vehicle was then searched under the cover of a staged incident.

Outcome: The Ninth Circuit upheld the search, finding no Fourth Amendment violation, reasoning that because there was probable cause beforehand, the staged setup did not render the search unconstitutional—even though it concealed the true investigative origin. Boyle & Jasari

This case stands as a cautionary tale: courts may validate contrived setups if probable cause exists, even when that setup was designed to obscure the true origin of the investigation.

2. Related Scholarship: The Problem of “Parallel Construction” in Criminal Investigations by Boyle & Jasari

While not a court decision, this legal analysis comprehensively outlines the implications and challenges of parallel construction:

Notable Example: It highlights Alverez-Tejeda as a clear example of how law enforcement can “reinvestigate” a suspect using fabricated events to mask the original, perhaps unconstitutional method of plugging into intelligence. Boyle & Jasari

This article supports the argument that courts have generally been reluctant to scrutinize or suppress evidence obtained through parallel construction—even under questionable origins.

Why Case Law on Parallel Construction Is Sparse

Despite significant scholarly and media attention—especially following revelations of intelligence-led law enforcement practices—there are very few reported cases directly addressing parallel construction in a critical or suppressive manner. Most cases involve investigations where probable cause was found through lawful means, leading courts to overlook the initial hidden source, as seen in Alverez-Tejeda.

What You Can Do:

Highlight the rarity of successful judicial challenges to parallel construction.

Emphasize that existing doctrine—like the “independent source” and “inevitable discovery” exceptions—often shields law enforcement tactics from suppression motions, even if they stem from concealed intelligence sources.

Case Law Spotlight: United States v. Alverez-Tejeda

Here’s a concise but powerful way to present it:

United States v. Alverez-Tejeda (9th Cir.): Agents, suspecting a drug offense, concocted a fake traffic accident and staged arrests to create a legitimate-looking basis for a vehicle search. Although deceitful, the Ninth Circuit deemed the search constitutional because probable cause existed before the ruse. This ruling underscores the deflection parallel construction affords law enforcement, even in deceptive operations. Boyle & Jasari

You might follow this with commentary like:

“This case starkly demonstrates how courts may permit fabricated investigative narratives so long as traditional safeguards—like probable cause—are technically satisfied.”

Why a Checklist Matters

Parallel construction thrives in the shadows, where vague discovery language and staged narratives obscure the true origins of evidence. For defense teams, spotting these patterns is not just strategy—it’s survival. The following checklist gives paralegals and attorneys a practical roadmap to detect when “evidence laundering” may be at play, and how to respond with precision, motions, and investigative pressure.

A Paralegal’s & Attorney’s Checklist: Detecting and Challenging Parallel Construction

1. Scrutinize Discovery Language

Action: Watch for vague phrases: “confidential source,” “anonymous tip,” or “information leading to…”

Purpose: These may obscure true investigative origins.

2. Trace Evidence Chain

Action: Examine search warrant affidavits closely for logical sequence or suspicious leaps.

Purpose: Discontinuities may signal hidden origins.

3. Investigate Methodology

Action: Request full disclosure on surveillance, data sources (e.g., Stingray, Hemisphere, FISA).

Purpose: Aim to reveal if intelligence-based data was repurposed.

4. Leverage Public Records Requests

Action: File FOIA or state public records requests for related surveillance mandates or tech use.

Purpose: Public records can expose hidden programs.

5. Challenge in Motions to Suppress

Action: Argue that recreated evidence remains tainted and not genuinely independent.

Purpose: Courts may agree—the exclusionary rule applies.

6. Demand Origin Transparency

Action: Cite cases like U.S. v. Daoud where courts mandated origin disclosure in surveillance investigations.

Purpose: Asserts Sixth Amendment confrontation rights.

7. Utilize Expert Support

Action: Engage surveillance or forensic experts to interpret tech-based evidence methods.

Purpose: May uncover discrepancies in alleged investigative channels.

8. Educate and Collaborate

Action: Train teams and collaborate with FOIA or privacy advocates who monitor such methods.

Purpose: Amplifies collective defense strategy.

9. Document Everything

Action: Maintain detailed logs of discovery anomalies, witness statements, and investigative steps.

Purpose: Builds record for appellate review if needed.

10. Keep Updated

Action: Monitor legislative reforms (e.g., FISA SAFE Act amendment) affecting surveillance warrants and transparency.

Purpose: Legislative shifts may affect how evidence must be handled.

New Checklist Item: Investigate Tiered Evidence Chains (U.S. v. Alverez-Tejeda)

Action: Look for signs that a seemingly legitimate investigative narrative (e.g., traffic stop, anonymous tip, staged accident) might mask a fabricated scenario.

Purpose: In United States v. Alverez-Tejeda (9th Cir.), agents staged a fake car accident to create a cover for searching a vehicle. The Ninth Circuit upheld the search, finding that pre-existing probable cause insulated the ruse from suppression. This case highlights how courts may allow contrived “parallel paths” so long as probable cause technically exists.

Conclusion

As paralegals and attorneys, recognizing parallel construction—and pushing back—is essential to protecting clients’ rights. Through vigilant document review, challenge filings, and strategic expert involvement, you can construct a robust defense that pierces the veil of surveillance secrecy. Your quest for truth is fundamental to preserving constitutional safeguards in an age of expanding government surveillance.